AI agents building security tests – architecture and prompts

The Detectify AI Agent Alfred fully automates the creation of security tests for new vulnerabilities, from research to a merge request. In its first six …

Frans Rosén and David Jacoby

The Facebook malware that spread last week was dissected in a collaboration with Kaspersky Lab and Detectify. We were able to get help from the involved companies and cloud services to quickly shut down parts of the attack to mitigate it as fast as possible.

Update #1: The attack is still ongoing but it has changed the flow and now steals a non-expiry access-token. Read more below.

It’s been a few days since Kaspersky Lab’s blog post about the Multi Platform Facebook malware that was spread through Facebook Messenger. At the same time as Kaspersky Lab were analyzing this threat, a few researchers where doing the same, including Frans Rosén, Security Advisor at Detectify.

After Frans saw David’s tweet about the blog post, he called David and asked why they were both doing the same job. Frans had a good point, so they started to compare notes and found out that Frans had actually analyzed some of the parts that David hadn’t. They decided to jointly write this second part of the analysis, which is going to describe the attack in detail.

Frans spent quite some time analyzing the JavaScript and trying to figure out how the malware was spreading, which might seem like a simple task but it wasn’t. There were multiple steps involved trying to figure out what the Javascript payloads did. Also, since the script dynamically decided when to launch the attack, it had to be monitored when the attackers triggered it.

The conclusions can be broken down into a few steps, because it’s not only about spreading a link, the malware also notifies the attackers about each infection to collect statistics, and enumerates browsers. We tried summarizing the steps as simply as possible below:

There are some interesting things in all these steps, so we will take a closer look below.

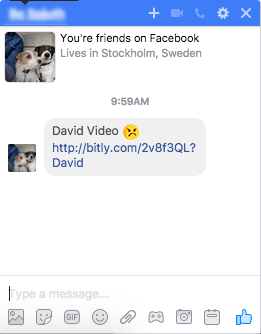

The message itself will consist of the first name of the user that gets the message, the word “Video” and one of these emojis selected at random:

together with a link created with a URL shortener.

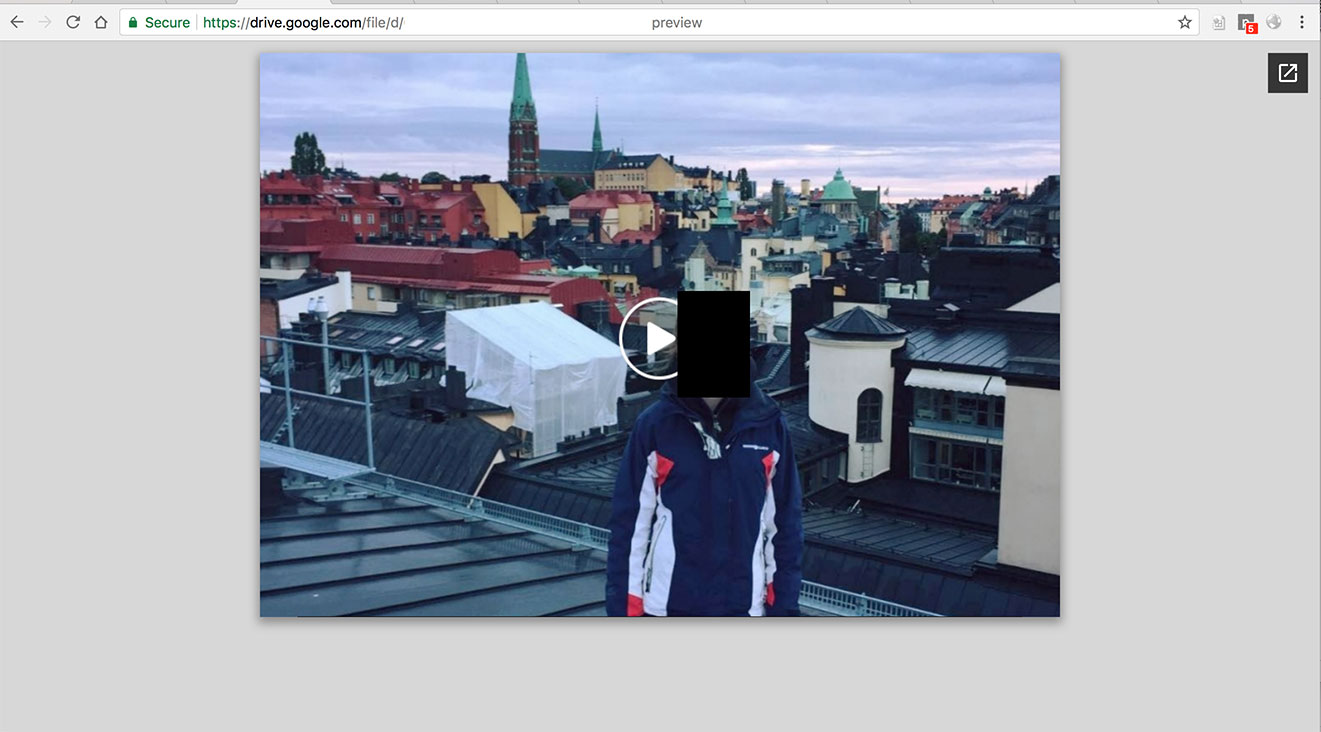

Clicking on the link will redirect the user to a URL on docs.google.com. This link is made by using the preview link of a shared PDF, most likely because it is the quickest way to get a large controlled content area on a legit Google domain with an external link.

The PDF itself is created using PHP with TCPDF 6.2.13 and then uploaded to Google Docs using Google Cloud Services. Clicking the ![]() will send us to a page containing details about the PDF file being previewed.

will send us to a page containing details about the PDF file being previewed.

The share settings are an interesting detail about the link created:

“Anyone can edit”. This configuration means that anyone who has the link can actually edit it. Looking at how these links spread, the attack reuses the same link for all the victim’s friends. One friend changing the access rights of the link could potentially prevent the attack from spreading to the victim’s other friends.

Another interesting detail is the user who created the file. Collecting a bunch of examples, we can see some patterns:

These were four links created for different victims, but three of them share the same IAM username (ID-34234) even though they were created using different Google Cloud Projects.

At the time of the attack, none of the URLs being linked from the PDF preview were blacklisted by Google.

After the Google Docs link is clicked, the user will go through a bunch of redirects, most likely fingerprinting the browser. Below, we will focus on Chrome as it is clear it was one of the targeted browsers for the spreading mechanism.

For the other browsers, ads were shown and adware was downloaded, read more about this under Landing Pages below.

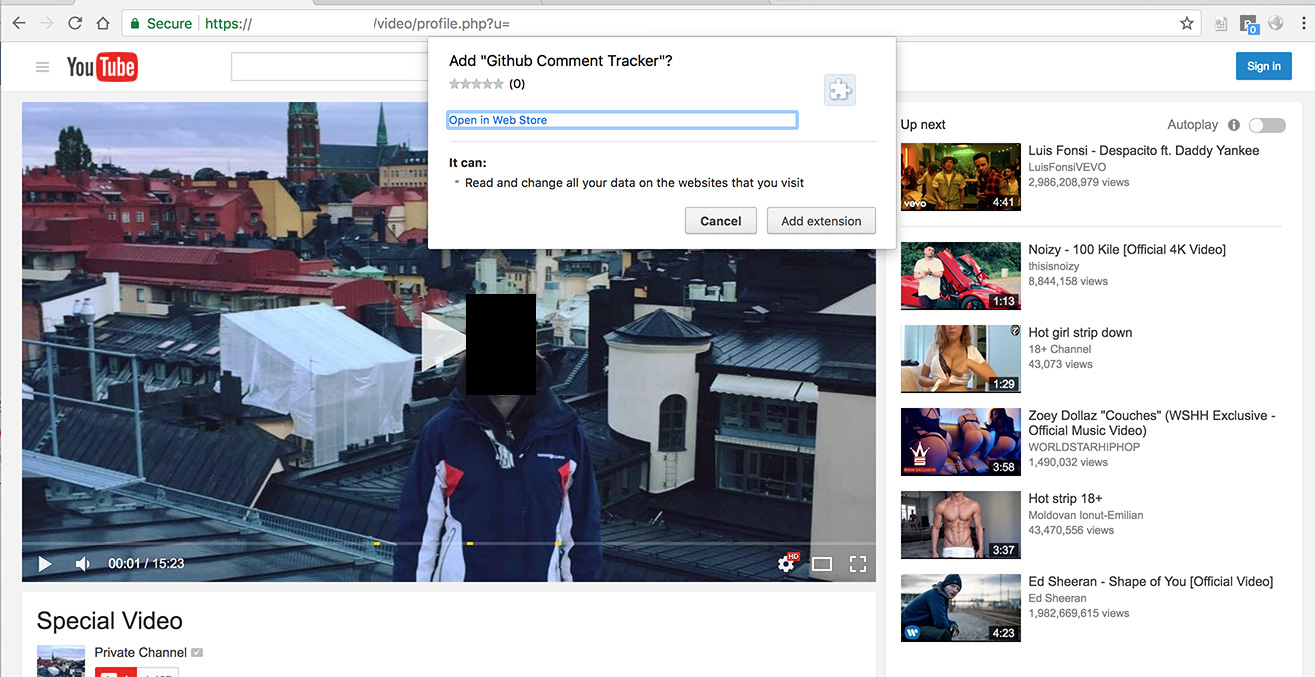

When using Chrome, you are redirected to a fake YouTube page. We noticed several different domains being used during the attack.

This page will also ask you to install a Chrome Extension. Since you can install a Chrome Extension directly on the page, the only action the victim had to perform was to click “Add extension”. No other interaction after that point was needed from the victim for the attack to spread further.

Several different Chrome Extensions were used. All of the extensions were newly created and the code was stolen from legit extensions with similar names. The differences in the extensions’ Javascript code were the background.js and a modification in the manifest.json.

The manifest was changed to allow control over tabs and all URLs, and also to enable support for the background script:

The background script was obfuscated differently in all the Chrome Extensions we found, but the basic concept looked like this:

This script was interesting in many ways.

First, the background script would fetch an external URL only if the extension was installed from the Chrome Webstore; a version installed locally using an unpacked extension would not trigger the attack.

The URL being fetched would contain a reference to another script. This script would be sent into a Javascript blob using URL.createObjectURL and then executed in the background script.

This new script from the blob would also be obfuscated. It looked like this:

What happens here is the following:

executeScript. This will run the Javascript in the context of the tab making the request, basically injecting an XSS that will trigger directly.When doing the research trying to identify the file that was being injected, I noticed that the attackers’ command and control server did not always return any code. My guess is that they were able to trigger when the attack should spread or not either manually or by specify when the attack should start.

To avoid sitting and waiting for a request to hit, I built my own pseudo extension doing the same thing as they did, but instead of triggering the code, I saved it locally.

Browsing around for a while, I noticed I got a bunch of hits. Their endpoint was suddenly returning back code:

The code returned was not obfuscated in any way, and had a simple flow of what it should do. It was fully targeted towards Facebook.

The script did the following:

facebook.comfb_dtsg.

Now, let’s move on to the most interesting parts of what the script did.

The script would like a page on Facebook that was hardcoded in the script. This was most likely used by the attackers to count the amount of infected users by keeping an eye on the amount of likes on this page.

Watching the page used during one phase of the attack, the amount increased fast, from 8,900 at one point:

and up to 32,000 just a few hours later:

It was also clear that they had control over when it should trigger or not using the script fetcher from the Command and Control, since the amount of likes increased at extremely varying speeds during the attack.

They also changed pages during the attack, most likely because they were closed down by Facebook.

Since the attackers now had an FQL-enabled access token, they could use the deprecated API to fetch the victim’s friends sorted by date of their online presence, getting the friends that were online at the time.

They randomized these friends picking 50 of them each time the attack would run only if the friends were marked as idle or online.

A link was then generated by a third domain, which only received the profile ID of the user. This site most likely created the PDF on Google Docs with the profile picture of the current victim and passed the public link back through a URL shortener.

After the link was fetched, a message was created randomly for each friend, but the link was reused among them.

Some parts of the injected code were never used, or were leftovers from previous attacks.

One part was the localization function to send messages in the proper locale of each friend. This was replaced by the random emoji in the live attack:

Some files on the domains used had some easy to guess PHP files still on the server such as login.php. That one exposed a login script to Facebook together with a hardcoded email address:

We noticed multiple versions of the injected Facebook script being used. At the end of the attack, the script only liked the Facebook page and did not spread at all. Also, the domain being used to gather access tokens was removed from the script.

As already mentioned, the script also enumerates which browser you are using. The Chrome extension part is only valid for victims using Google Chrome. If you are using a different browser, the code will execute other commands.

What makes this interesting is that they have added support for most of the operating systems; we were not able to collect any samples targeting the Linux operating system.

All of the samples that we collected where identified as Adware, and before the victim landed on the final landing page, they were redirected through several tracking domains displaying spam/ads. This is an indication that the people behind this scam were trying to earn money from clicks and distributing spam and ads.

MD5 (AdobeFlashPlayerInstaller.dmg) = d8bf71b7b524077d2469d9a2524d6d79

MD5 (FlashPlayer.dmg) = cfc58f532b16395e873840b03f173733

MD5 (MPlay.dmg) = 05163f148a01eb28f252de9ce1bd6978

These are all fake Adobe Flash updates, but the victim ends up at different websites every time, it seems that they are rotating a set of domains for this.

MD5 (VideoPlayerSetup_2368681540.exe) = 93df484b00f1a81aeb9ccfdcf2dce481

MD5 (VideoPlayerSetup_3106177604.exe) = de4f41ede202f85c370476b731fb36eb

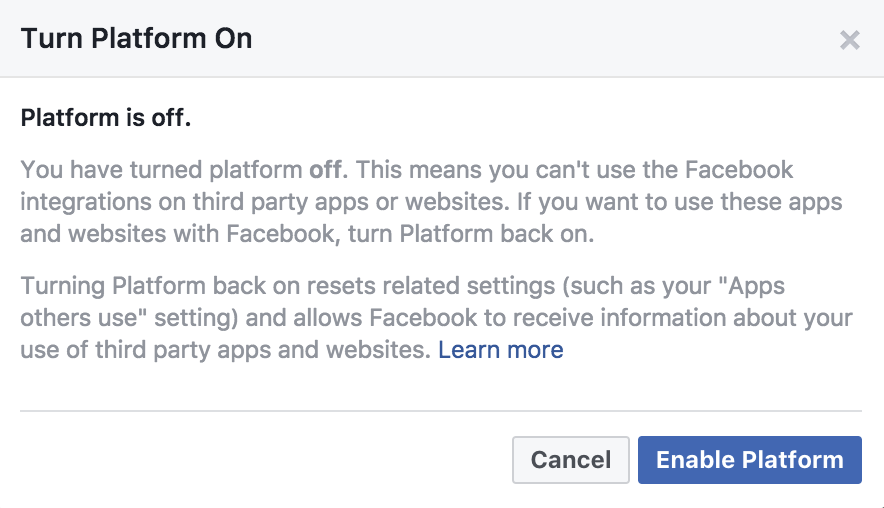

The Google Chrome Security Team has disabled all the malicious extensions, but when the attackers infected your Facebook profile they also stole an access-token from your Facebook account. It seems like the expiry time of this token might have been limited, but the scope it was giving access to was huge, since the token is mainly used for the “Facebook for Android”-app. With this access-token the attackers could gain access to your profile again, even if you have for example: Changed your password, signed out from Facebook or turned off the platform settings in Facebook:

We are currently discussing this with Facebook but at the moment it seems like there is no simple way for a victim to revoke the token the attackers stole. Hopefully they did not do anything with the token before it expired.

It’s highly recommended that you update your Anti Virus solution because the malicious domains and scripts have been blocked.

The attack relied heavily on realistic social interactions, dynamic user content and legit domains as middle steps. The core infection point of the spreading mechanism above was the installation of a Chrome Extension. Be careful when you allow extensions to control your browser interactions and also make sure you know exactly what extensions you are running in your browser. In Chrome, you can write chrome://extensions/ in your URL field to get a list of your enabled extensions.

We would like to give out special thanks to the following people who helped us shut down the attack as much as possible:

Without your help this campaign would have been much more widespread. Thank you for your time and support! Also thanks to @edoverflow for poking at the obfuscated code at the same time as us.

Update #1: We noticed on the 31st of August that a new form of this spreading mechanism was being used. This time it was targeting publicly shared links on Facebook, tagging the friends of the victim, instead of using Facebook Messenger.

dyn, b_dtsg) and profile_id from the victim.console.log in their code to show an example of the shortened link.comment_text: "@[1234:Test User] @[12345:Test User 2]"The end result of this by looking at the activity page in Facebook will look something like this:

The access token they stole has a huge scope surface, meaning they can access, delete, modify and create huge amount of private data from the victim, such as:

Most importantly. This time, the token they steal has a non-expiry date. This means that there is no way to revoke this access token if you have been infected. We are currently waiting for Facebook to respond on how they will solve this issue as the victims currently cannot do anything about it.

The Detectify AI Agent Alfred fully automates the creation of security tests for new vulnerabilities, from research to a merge request. In its first six …

Combining response-type switching, invalid state and redirect-uri quirks using OAuth, with third-party javascript-inclusions has multiple vulnerable scenarios where authorization codes or tokens could leak to …